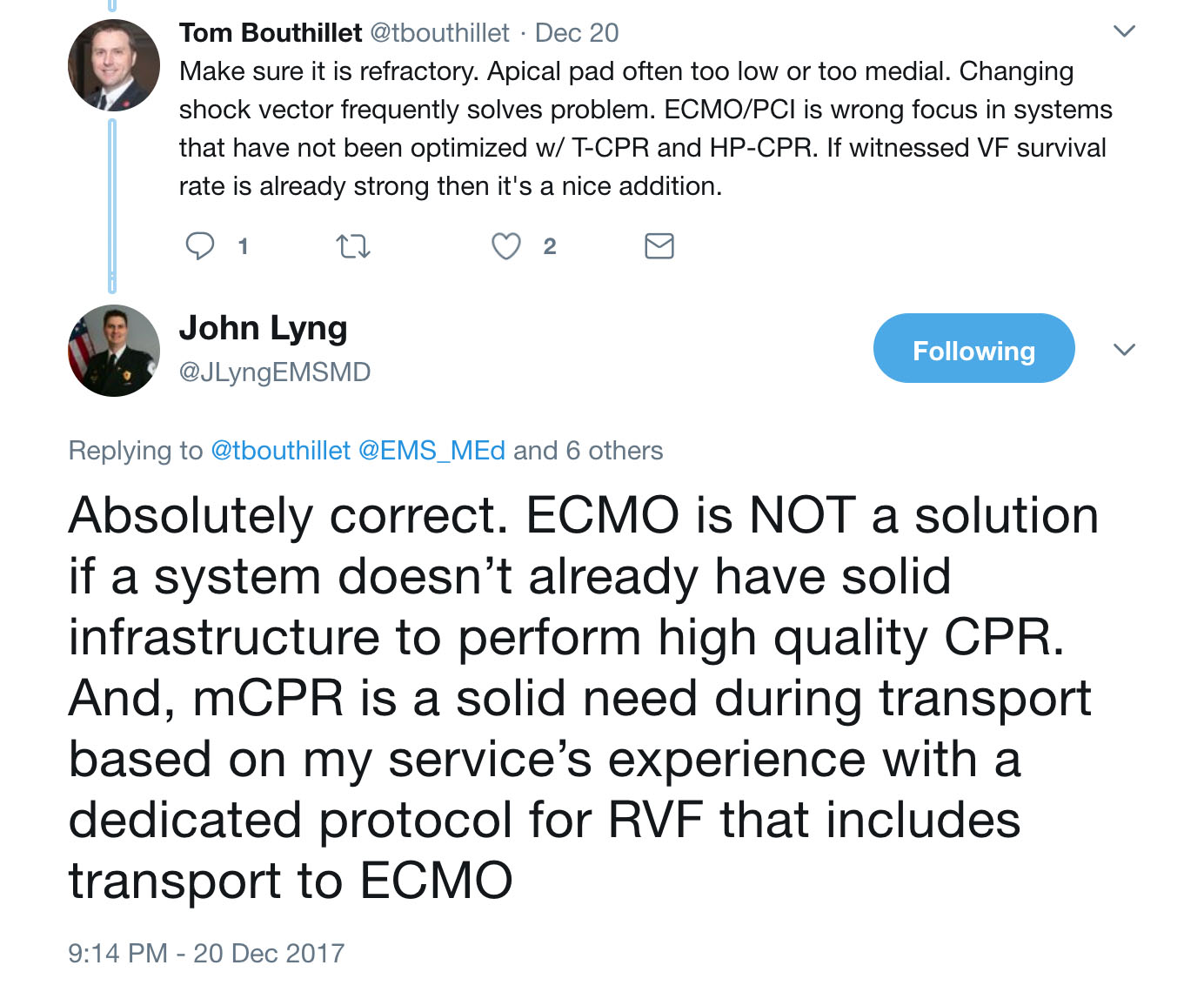

While the table above by no means represents a rigorously-derived summary such as would be included in a systematic review, one simple observation is that each device has predominantly been evaluated in the clinical setting for which it was initially developed: LMA devices (i-gelTM and LMA-SupremeTM) in the operating room and LT in out-of-hospital studies. This difference in intended setting was the topic of a subset of comments left on the discussion forum post:

“We switched to igel for a one year trial. So far results are mixed. Our medical director doesn't like the long list of manufacturers contraindications. i.e. Non-fasted patients for routine and emergency anaesthetic procedures. Patients with an ASA or Mallampati score of III and above. Trismus, limited mouth opening, pharyngo-perilaryngeal abscess, trauma or mass.If this device is a rescue airway for an unsuccessful ETI. If it was an unsuccessful intubation attempt due to difficulties or trauma, an igel is contraindicated. Not to say the king was any better or worse but it didn't have the box contraindications. Would love some more provider insight.” - Joshua

“This is a great discussion and where we need to focus on the context of the airway's application. First, the Mallampati scale holds virtually no relevance to emergency situations out of hospital. By definition, many of our patients will be Class III and above due to the presence of an acute, life threatening condition. In fact, the lack of visualization of the posterior oropharynx (Mallampati 4) might serve as an actual indication for these devices!” – Ben Lawner

“Let me start with a disclosure. I'm an anesthesiologist and paramedic. Our system in Upstate NY is a King system and I would like us to become an iGel system. The King was designed as a rescue airway tool for EMS. LMAs in general are a hospital tool that has come over and been adapted to EMS as a rescue device. I'm just guessing here, but my hospital system probably uses > 500 disposable LMAs for every one King airway that comes into our Level 1 quaternary academic medical center. The market for LMA manufacturers is dramatically bigger than the market for King airways.

If we polled physicians that manage airways in the US and asked what type of airway is available to them as a SGA for rescue purposes, what percentage would say King airways? I am currently not aware of any hospitals that purchase King Airways as rescue devices and they certainly don't buy them as primary airway devices. In fact, the only reason most anesthesiologists know about King airways is because we are occasionally called up the EM department to switch them out to an ETT.

I'm not aware of any direct evidence comparing the two. It's pretty obvious to me though that less cuffs and balloons means less chance of malfunction in a uncontrolled environment. The iGel can be switched out to an ETT in a much safer manner once oxygenation has been achieved. The iGel has nothing that breaks or tears. I could see the King being preferred in a patient who required very high peak inspiratory pressures to achieve adequate ventilation, but that's pretty nuanced for a rescue device.

Joshua, your medical director won't see those contraindications change anytime soon. EMS is likely the King airway's near total business line. EMS is a tiny portion of the iGel's manufacturers business, so they probably won't bother to make that investment. I can assure you that LMAs are used as rescue devices in CICO or CICV (cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate/ventilate) situations in hospitals around the world on a daily basis. LMAs have saved more than a few patient's lives in my practice and will continue to do so. I'll let you know when I start using the King, but don't hold your breath.” – Christopher Galton

Although not have been developed specifically for prehospital use, the LMA-devices are widely used as rescue devices in emergency and prehospital settings, including in cases of severe facial trauma [19,20]

Facilitation of intubation:

In his commentary above, Dr. Galton brings up an important point that was echoed by other commenters – the ability to intubate through the device rather than needing to remove the device to intubate.

“IGel and King used in SW Ohio. Prefer IGel...it’s easier to use and capable of exchange for ETT in Hospital without removing the device. King has to be removed for patient to be intubated. I’m intrigued, though, by the Intubating King assuming it eventually becomes available in US.” – Josh B

“We're an iGel shop. I moved us from the King several years ago and we've been pleased. I disliked the airway maceration I saw in the ED when I eventually swapped out the King for an ET. – Jeff Jarvis

With its current design, the LT must be removed in order for endotracheal intubation to occur. One concern for any airway manipulation that occurs prior to endotracheal intubation is whether a supraglottic device may cause enough perilaryngeal tissue trauma to make subsequent endotracheal intubation more difficult. In a randomized comparison of the i-gelTM, LMA SupremeTM and LTS-D devices in the operating room, the authors evaluated the incidence of “airway morbidity” caused by each of the devices [3]. They assessed how often the device had blood on the outside of it after removal and whether patients later complained of sore throat or dysphagia. In comparison with the i-gel (13%) or LMA-supreme (13%), the LTS-D more often had blood on the outside of the device (37.5%, p=0.006). This correlated with a significant increase in the incidence of subsequent sore throat or dysphagia. Whether this type of “airway morbidity” has any predictive value at all for increased difficulty in airway securement after device removal is unclear.

The ventilation port of i-gelTM airway is large enough to facilitate subsequent endotracheal intubation through the device [21]. This ideally should be performed using fiber-optic guidance as blind endotracheal intubation through an i-gel has a low success rate at least in a manikin study [22]. Exchange of a King-LT over a gum-elastic bougie should not be pursued; in one cadaver, this led to penetration of the right aryepiglottic fold by the bougie which subsequently ended up in the soft tissues of the neck [23]. Intubation around the King airway using video laryngoscopy and a gum-elastic bougie has been described [24].

Safeguards are key.

One group of commenters made the important point that no matter which supraglottic was used, correct placement and adequate oxygenation and ventilation must be ensured:

“Either as long as you use waveform capnography to confirm placement! No airway is foolproof....must be confirmed!” – Veer Vithalani

“Veer is spot on about requiring EtCO2 just like we do for intubation (great paper!).” – Jeff Jarvis

“I have both King and iGel at my agencies. Both are widely used and accepted by my crews.

We have slowly moved toward the iGel for a few reasons:

1. No balloon to inflate

2. No added pressure (from a balloon) in the hypopharynx which doesn't impede carotid flow (pig and cadaver studies)

3. Gastric port (12 Fr) can be inserted into the stomach (except for size 1)

Downsides of the iGel:

1. No gastric port for the size 1

2. Packaging for the iGel consumes a lot of space compared to king

3. Cannot use commercial tube holders to stabilize the pediatric sizes.

a. Smaller sizes do not have the strap - adult sizes do.

b. Without the strap the iGel may "pop" out ever so slightly and the provider may not realize it

4. Intersurgical requires that the agency sign a waiver since the product was not intended for field airway use

My overall feeling is that iGel is preferred, yet I like the King and agree with what Veer said in his comment.”- Peter Antevy

“Agree with the comments about the absolute need for capnometry. Our first responders are using a colormetric device and our paramedics use waveform capnometry. We do have prolonged resuscitation times (we generally do not transport unless we have ROSC and have stabilized the patient). As with any device there are considerations, however training and feedback to providers seem to increase the success of its use.” – Dena Smith

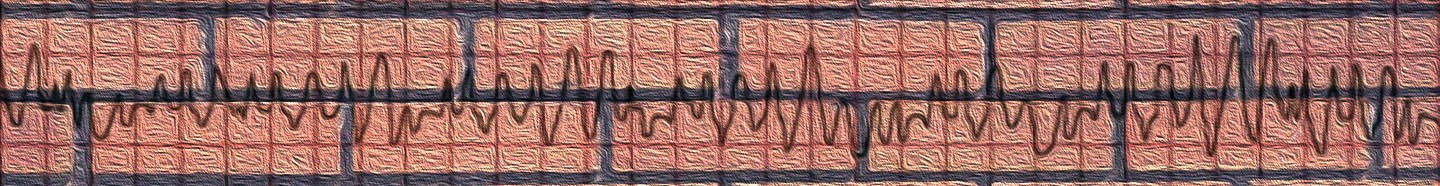

As voiced in the commentary by Dr. Vithalani, as with endotracheal intubation, supraglottic airways should always be confirmed with continuous in-line capnography to confirm both initial placement as well as safeguard against unrecognized dislodgment of the device. Supraglottic airways should be secured, as they will dislodge with similar force to an endotracheal tube [24]. Vithalani et. al. studied the incidence of unrecognized failed airway management using a supraglottic airway device (King LTS-D) within their EMS system [25]. They retrospectively reviewed continuous capnography tracings of 344 the supraglottic airway attempts. Objective successful airway placement was defined as a sustained 4-phase end-tidal waveform greater than or equal to 5 mmHg for the duration of patient care, while subjective successful placement was defined as documentation of successful placement by the EMS provider. They found that only 85.1% of subjectively successful SGA placements met objective criteria for successful placement. Conversely, 4 of 28 (14%) of SGA airways that were removed because they were deemed failed by the providers actually met the objective criteria for success. The main conclusion of this paper is an important one:

“This study points to the critical necessity for objective measurement of airway management utilizing a supraglottic airway device… adequate education, training and quality assurance processes must be in place to ensure appropriate use and interpretation of continuous waveform capnography by EMS providers.”

Agreement on type of device, adequate system-wide training on its use and subsequent quality review to ensure that it is used with proper indications and quality controls remain both barriers and requirements for effective implementation or system-wide change:

“We've used intubating LMAs (disposable), Kings and now Air Qs. All work fairly well. In my opinion the most important thing is train intensively, QA thoroughly and make sure your paramedics have a healthy respect for the difficult airway.” - Marc Restuccia

“Currently using King LT, which we switched to from Combi-tube a number of years ago. Contemplating a switch to iGel, based on reported simplicity of use and reported good results. One challenge is getting 2 EMS medical directors and 13 EMS agencies to come to agreement for a system-wide change.” – Paul Rostykus

Patient-centered outcomes

“In terms of evidence base, there's really not a lot when it comes to the best "backup airway" decision based upon patient centered outcomes. The supraglottic airways can certainly temporize a difficult situation, but I struggle with evidence based recommendations. The King Airway seems quite popular, but I've encountered more than a few problems with dislodgement and ineffective ventilation. In terms of tried and true airways, the "LMA advantages" include: ease of insertion, quick deployment, and relative lack of side effects. LMAs have been used successfully for quite some time and are arguably the most well studies. Granted, we adapt airways for prehospital use, and there really is no "one size fits all" when it comes to the airway management of sick patients in the out of hospital setting.” – Ben Lawner

As voiced by Dr. Lawner, the supraglottic debate is similar to many clinical situations in prehospital care where there are few evidence-based recommendations to support clinical decision making based on patient-centered outcomes. Many aspects discussed with respect to supraglottic airways – such as of ease of use and successful placement or effect on carotid blood flow – may be useful surrogates for patient-centered outcomes but fall very short of where we as a specialty need them to be. Ease of use is basically an operational outcome, but quality in medicine is really about patient outcome and from this perspective, the debate of supraglottic proportions continues.

Take Home

The most commonly used devices amongst our readers are the i-gelTM, King LT, and LMA-SupremeTM. Current data regarding overall ease of use find overall high success rate within two attempts for all devices. Regardless of which device is used, there must be rigorous training not only on placement, but continuous end-tidal capnography as a means to ensure initial placement and prevent unrecognized device dislodgment.

Summary of discussion comments by EMS MEd Editor, Maia Dorsett MD, PhD (@maiadorsett)

For an excellent review and more in-depth discussion of supraglottic airways, we highly recommend Darren Braude’s talk available through the EMS Medicine Live site: http://www.ems-medicine.com/single-post/2016/05/31/Extraglottic-Airways-Updates-Controversies

References

1. Ostermayer, D. G., & Gausche-Hill, M. (2014). Supraglottic airways: the history and current state of prehospital airway adjuncts. Prehospital Emergency Care, 18(1), 106-115.

2. Gatward, J. J., Cook, T. M., Seller, C., Handel, J., Simpson, T., Vanek, V., & Kelly, F. (2008). Evaluation of the size 4 i‐gel™ airway in one hundred non‐paralysed patients. Anaesthesia, 63(10), 1124-1130.

3. Russo, S. G., Cremer, S., Galli, T., Eich, C., Bräuer, A., Crozier, T. A., ... & Strack, M. (2012). Randomized comparison of the i-gel™, the LMA Supreme™, and the Laryngeal Tube Suction-D using clinical and fibreoptic assessments in elective patients. BMC anesthesiology, 12(1), 18.

4. Fenner, L. B., Handel, J., Srivastava, R., Nolan, J., & Seller, C. (2014). A Randomised Comparison of the Supreme Laryngeal Mask Airway with the i-gel During Anaesthesia. J Anesth Clin Res, 5(440), 2.

5. Francksen, H., Renner, J., Hanss, R., Scholz, J., Doerges, V., & Bein, B. (2009). A comparison of the i‐gel™ with the LMA‐Unique™ in non‐paralysed anaesthetised adult patients. Anaesthesia, 64(10), 1118-1124.

6. Weber, U., Oguz, R., Potura, L. A., Kimberger, O., Kober, A., & Tschernko, E. (2011). Comparison of the i‐gel and the LMA‐Unique laryngeal mask airway in patients with mild to moderate obesity during elective short‐term surgery. Anaesthesia, 66(6), 481-487.

7. Mitra, S., Das, B., & Jamil, S. N. (2012). Comparison of Size 2.5 i-gel™ with ProSeal LMA™ in anaesthetised, paralyzed children undergoing elective surgery. North American journal of medical sciences, 4(10), 453.

8. Jagannathan, N., Sommers, K., Sohn, L. E., Sawardekar, A., Shah, R. D., Mukherji, I. I., ... & Seraphin, S. (2013). A randomized equivalence trial comparing the i‐gel and laryngeal mask airway Supreme in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 23(2), 127-133.

9. Theiler, L. G., Kleine-Brueggeney, M., Kaiser, D., Urwyler, N., Luyet, C., Vogt, A., ... & Unibe, M. M. (2009). Crossover comparison of the laryngeal mask supreme™ and the i-gel™ in simulated difficult airway scenario in anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 111(1), 55-62.

10. Das, B., Mitra, S., Jamil, S. N., & Varshney, R. K. (2012). Comparison of three supraglottic devices in anesthetised paralyzed children undergoing elective surgery. Saudi journal of anaesthesia, 6(3), 224.

11. Bamgbade, O. A., Macnab, W. R., & Khalaf, W. M. (2008). Evaluation of the i‐gel airway in 300 patients. European Journal of Anaesthesiology (EJA), 25(10), 865

12. Wharton, N. M., Gibbison, B., Gabbott, D. A., Haslam, G. M., Muchatuta, N., & Cook, T. M. (2008). I‐gel insertion by novices in manikins and patients. Anaesthesia, 63(9), 991-995.

13. Middleton, P. M., Simpson, P. M., Thomas, R. E., & Bendall, J. C. (2014). Higher insertion success with the i-gel® supraglottic airway in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation, 85(7), 893-897.

14. Hagberg, C., Bogomolny, Y., Gilmore, C., Gibson, V., Kaitner, M., & Khurana, S. (2006). An evaluation of the insertion and function of a new supraglottic airway device, the King LT™, during spontaneous ventilation. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 102(2), 621-625.

15. Gahan, K., Studnek, J. R., & Vandeventer, S. (2011). King LT-D use by urban basic life support first responders as the primary airway device for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation, 82(12), 1525-1528.

16. Wyne, K. T., Soltys, J. N., O’Keefe, M. F., Wolfson, D., Wang, H. E., & Freeman, K. (2012). King LTS-D use by EMT-intermediates in a rural prehospital setting without intubation availability. Resuscitation, 83(7), e160-e161.

17. Frascone, R. J., Wewerka, S. S., Griffith, K. R., & Salzman, J. G. (2009). Use of the King LTS-D during medication-assisted airway management. Prehospital Emergency Care, 13(4), 541-545.

18. Guyette, F. X., Wang, H., & Cole, J. S. (2007). King airway use by air medical providers. Prehospital Emergency Care, 11(4), 473-476.

19. Baratto, F., Gabellini, G., Paoli, A., & Boscolo, A. (2017). I-gel O 2 resus pack, a rescue device in case of severe facial injury and difficult intubation. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

20. Häske, D., Schempf, B., Niederberger, C., & Gaier, G. (2016). i-gel as alternative airway tool for difficult airway in severely injured patients. The American journal of emergency medicine, 34(2), 340-e1.

21. Michalek, P., Hodgkinson, P., & Donaldson, W. (2008). Fiberoptic intubation through an I-gel supraglottic airway in two patients with predicted difficult airway and intellectual disability. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 106(5), 1501-1504.

22. Michalek, P., Donaldson, W., Graham, C., & Hinds, J. D. (2010). A comparison of the I-gel supraglottic airway as a conduit for tracheal intubation with the intubating laryngeal mask airway: a manikin study. Resuscitation, 81(1), 74-77.

23. Lutes, M., & Worman, D. J. (2010). An unanticipated complication of a novel approach to airway management. The Journal of emergency medicine, 38(2), 222-224.

24. Klein, L., Paetow, G., Kornas, R., & Reardon, R. (2016). Technique for exchanging the King Laryngeal Tube for an endotracheal tube. Academic Emergency Medicine, 23(3).

25. Carlson, J. N., Mayrose, J., & Wang, H. E. (2010). How much force is required to dislodge an alternate airway?. Prehospital Emergency Care, 14(1), 31-35.

26. Vithalani, V. D., Vlk, S., Davis, S. Q., & Richmond, N. J. (2017). Unrecognized failed airway management using a supraglottic airway device. resuscitation, 119, 1-4.

![Pan et. al. Table 3 [Reference 7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58174dbb6a496367e36143b1/1505327105970-YJPOUOUJET70KQTL4IBT/Pan_Table3.jpg)