by Aurora Lybeck, MD and M. Riccardo Colella, DO

Abstract: First responders, including Emergency Medical Services (EMS), fire departments, and law enforcement officers (LEOs), are often the first to respond to suspected opioid overdoses. The heroin epidemic has been worsening throughout the US and Canada, from coast to coast and in every state and province. The recent increase in synthetic opioid abuse and heroin contaminants can raises additional safety concerns for first responders and strains local resources. We suggest an emphasis on provider safety including personal protective equipment (PPE) and awareness of potential first responder exposure. Patient care for suspected overdoses should focus on respiratory support, transporting patients refractory to initial scene care, and ensuring appropriate naloxone dosage and adequate supply on each responding unit. Synthetic opioids in a local area can create a surge in overdose calls that has the potential to overwhelm available emergency resources and supplies, akin to a mass casualty event. EMS systems may mitigate potential strain on local resources by awareness and monitoring of local epidemiologic patterns, preparation, and collaboration with local agencies.

Background: The number of heroin related deaths and overdoses have significantly increased over the past decade. Overdose deaths involving heroin more than tripled in the US from 2010 to 2014, and are anticipated to be even higher given the rapidly changing epidemic [1, 2, 3]. Numerous federal organizations such as The Center for Disease Control (CDC), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS), and the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA), continue to gather and report on these data as this epidemic burgeons. In 2016, the DEA declared prescription drugs, heroin, and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, the most significant drug related threat to the US.. Outbreaks of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids have contributed to surges in overdoses rates and deaths. In 2016 and early 2017, several EMS agencies experienced significant increases in overdose related call volumes. Multiple cities have witnessed overdose “outbreaks” which can overwhelm local EMS resources, akin to a mass causality event. For instance, in February 2017, EMS agencies in Louisville, Kentucky received 151 overdose calls within four days, with 52 of those calls occurring within 32 hours. [4] Medical examiner data from similarly affected areas reflects similar surges in overdose deaths, raising suspicion that fentanyl and other synthetic opioids may be at least partially to blame. [5, 6]. High-potency opiates require higher doses of naloxone for reversal. A retrospective study of NEMSIS data from 2012-2015 found that among patients receiving prehospital naloxone, the percent of patients receiving multiple doses increased from 14.5% in 2012 to 18.2 % in 2015, anoverall increase of 25.8 % suggesting increased infiltration of the opiod market by high-potency synthetics [7].

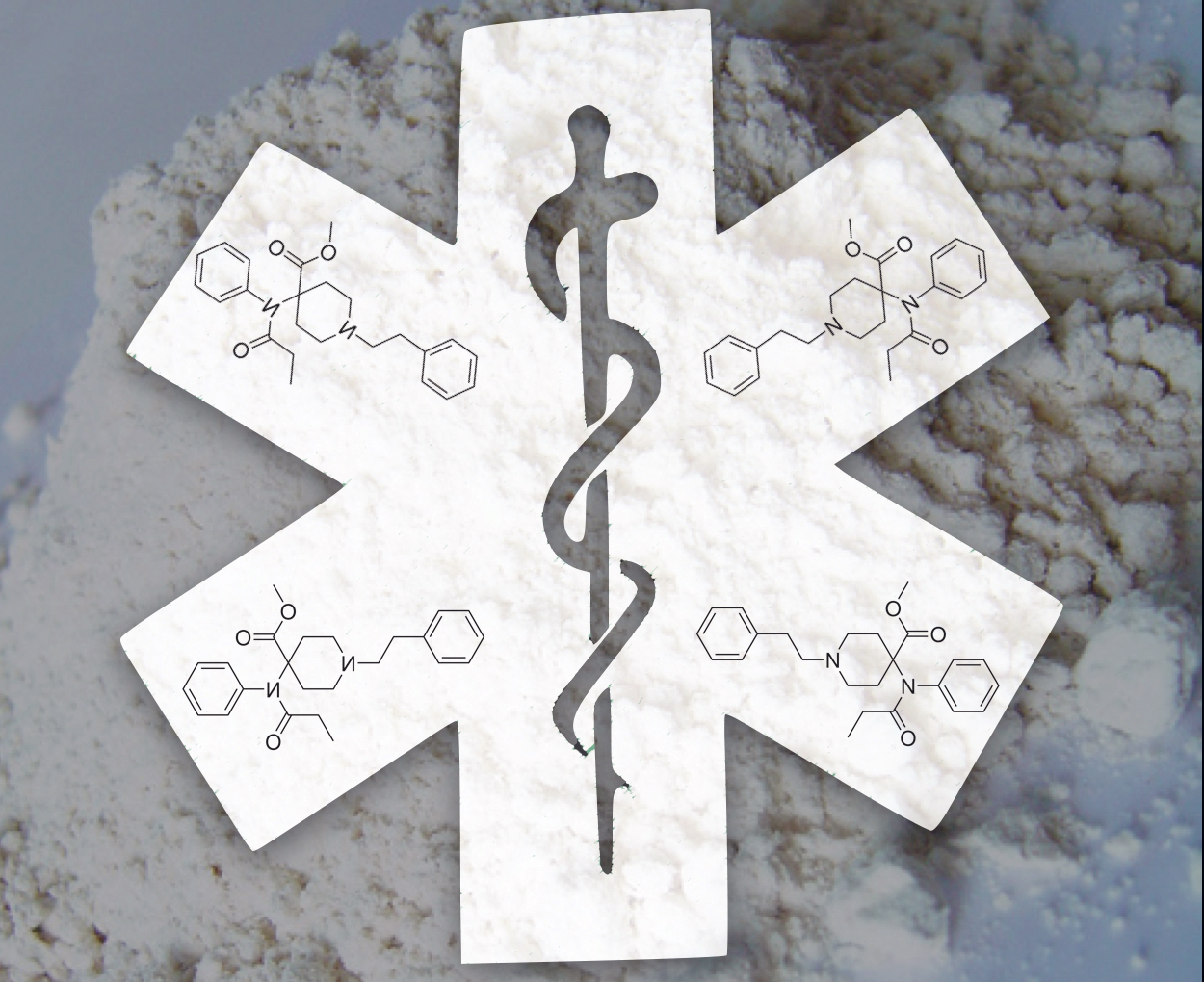

Fentanyl is considered 100 times more potent than morphine and 600 times more lipid soluble, subsequently increasing brain absorption. Illicitly produced synthetic opioids include non-pharmaceutical fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and novel synthetic opioids [8]. Synthetic opioid overdose outbreaks have occurred historically on a smaller scale, as evidenced by the China White (3-methylfentanyl) in the US in the 1980’s [9] and several hundred fentanyl deaths across the US in the mid 2000’s [10,11]. The CDC reports a marked increase in deaths involving synthetic opioids since 2013 [2, 12]. Since Pharmaceutical fentanyl prescription rates (primarily fentanyl patches) remained relatively stable in comparison, the etiology of this surge is not prescription fentanyl. [12, 13]. Synthetic opioids are often found as a heroin contaminant or are sold in pill form [14, 15]. Hundreds of thousands of counterfeit pills have been entering the US and Canadian drug market, many of which contain fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, some at lethal doses in a single pill [12-18].

The fentanyl analog carfentanil is considered 10,000 times more potent than morphine and 100 times more potent than fentanyl [5, 6, 19], and is reported in medical examiner overdoses cases across the US and Canada. In 2002, an unknown aerosolized “gas” was used by Russian special operations forces in an attempt to rescue 800 hostages held in a theater by Chechnan rebels. Sadly, at least 125 hostages were killed, and years later carfentanil and remifentanil were positively identified as likely agents in post-mortem samples [20]. Other synthetic opioids including various fentanyl analogs, (such as MT-45, AH-7921 and an isomer U-47700) are present in the illicit marketplace and have all been confirmed in deaths in the US, Canada, and Europe [21-24]. Once novel synthetic drugs appear in the market, there is often a significant time delay to the development of an assay for identification in post-mortem samples. By the time the chemical is identified with reliability, either from post mortem samples or seized drug samples, the synthetic drug manufacturers often have already flooded the market with a new compound. Consequently, first responders may encounter either an affected patient or a drug exposure in the field before it has been identified.

Provider Safety and Personal protective equipment (PPE)

The most commonly used PPE for first responders includes nitrile gloves and occasionally eye protection, escalating to other types of PPE as situationally indicated. In a 2017 descriptive surveillance study, data collected from 572 EMS workers who sought treatment in emergency departments (EDs) between 2010-2014 demonstrated that exposures to harmful substances were the second leading occupational injury (behind strains and sprains). The authors recommended new and enhanced efforts to prevent EMS worker injuries and exposures to harmful substances [25]. The concept of evolving and improving our use of PPE is not new to healthcare providers. Diseases such as Ebola and SARS have spurred additional training and use of PPE, and the use of PPE should be continually readdressed in the face of new threats to provider safety.

The DEA released a warning in June 2016 to the police and public regarding fentanyl exposures after two law enforcement officers (LEOs) experienced overdose symptoms after exposure to airborne particulate from a “tiny amount” of white powder. This warning was later expanded to include all first responders, with a guide for prehospital providers released in Jun 2017 [26, 27]. Heroin found in the white powder form (predominantly, with some regional variability) and is visually indistinguishable from most synthetic opioids (1). Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids in the white powder form may put first responders at risk by mucous membrane contact, inhalation of airborne particulate, and potentially skin contact. Toxic doses of carfentanil in particular pose a significant risk to first responders in small amounts, some as little as a few grains of salt. The Acting DEA Administrator stated in reference to synthetic opioids: “I hope our first responders- and the public- will read and heed our health and safety warning. These men and women have remarkably difficult jobs and we need them to be well and healthy” [19].

With increasing concern for first responder safety and exposures, the Justice Institute of British Colombia, in conjunction with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), British Colombia Emergency Health services, and Vancouver Fire Rescue services, and other collaborating services created an innovative website at www.fentanylsafety.com. Included are resources for all levels of first responders outlining specific considerations for LEOs, firefighters, EMS, and Hazmat personnel. Within the EMS recommendations is a guide specific for fentanyl/synthetic overdose education, treatment guidelines, field risk assessment, donning and doffing PPE including N95 masks, and protocol recommendations for self-administration of naloxone in the event of symptomatic exposure. NIOSH, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, provides similar PPE recommendations for first responders, found at www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/risk.html. Though exposures may be uncommon, the prehospital environment can be unpredictable and providers may unintentionally encounter substances while caring for patients. First responders should be intimately aware of risk for contact with, disturbing, or aerosolizing any powders on patients, their clothing, and surroundings. If such substances are on or near the patient, first responders should at minimum add respiratory precautions such as facemasks to routine PPE, and consider NIOSH recommendations for full PPE. As always, scene safety remains paramount.

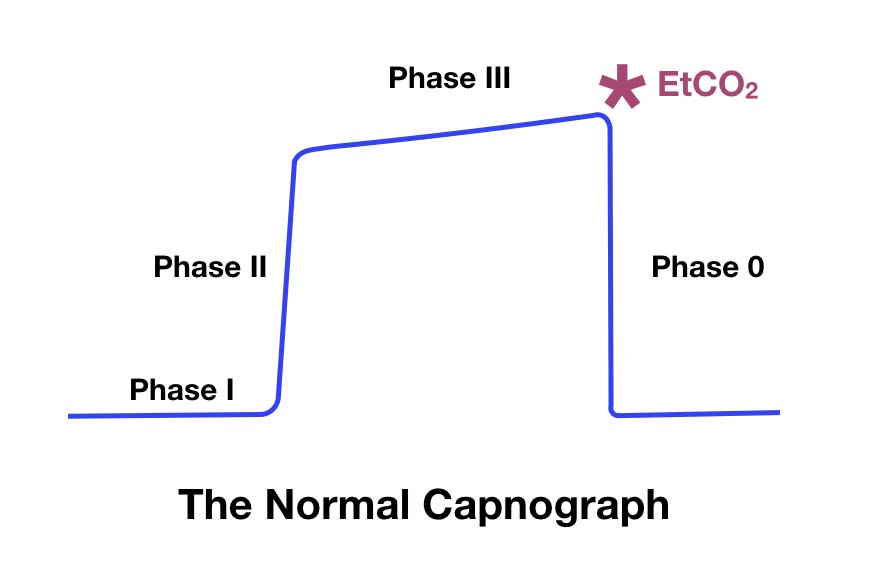

Respiratory support

Synthetic opioids overdoses should be treated initially the same as all patients with respiratory failure and/or suspected opioid overdoses with a pulse, primarily with effective Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM) ventilations. Ensuring an open airway, providing respiratory support, and monitoring circulation remain cornerstones of patient care for all levels of EMS providers. Nasal or oral airway adjuncts and oxygen administration to correct hypoxemia should also be used when indicated. Almost one quarter of synthetic opioid overdose patients described in one hospital based case series required advanced respiratory support for persistent hypoxemia despite high doses of naloxone, and repeat respiratory arrest after cessation of naloxone infusion [14]. While the current focus for lay persons and law enforcement is rapid naloxone administration for suspected opioid overdoses, EMS providers are experts in the “ABCs”. A full patient assessment, high quality basic skills such as use of airway adjuncts, BVM, and respiratory support is imperative.

Naloxone

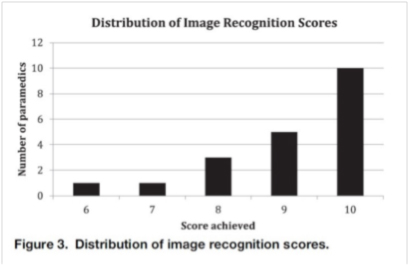

Naloxone is a high affinity mu-opioid receptor antagonist which acts on the central nervous system. It can be given to suspected opioid overdoses to reverse respiratory depression in the prehospital setting. For routine suspected opioid overdose, there are no definitive studies that have determined the optimal dose of naloxone to administer. Recommendations for initial dose can vary 10-fold based on reference and medical specialty. In general, emergency medicine and anesthesia references suggest higher doses (0.4mg) while medical toxicology and general medicine references suggest lower doses (0.04mg) [28]. The naloxone nasal atomizer devices currently in use by most first responders and bystanders is delivered in either 2mg or 4mg single dose sprays. Intranasal (IN) naloxone has an approximate bioavailability of only 4%, significantly lower than intramuscular (IM) and intravenous (IV) naloxone [29]. One prehospital study found that 2mg IN naloxone was not inferior to 0.4mg IV naloxone at reversing opioid induced apnea or hypopnea [30].

There is some concern that following naloxone administration and reversal of opioid overdose, patients may have adverse events such as pulmonary edema, precipitation of withdrawal symptoms, vomiting, or aspiration pneumonitis. In a one year prospective study in Norway, EMS witnessed vomiting in only 9% of patients who received prehospital naloxone [31]. A retrospective study in Pittsburgh found a lower rate of adverse events following naloxone administration with vomiting in only 0.2% of patients [32]. Novel synthetic opioid overdose cases have demonstrated a variety of adverse events during or after naloxone administration, including pulmonary edema and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage [14, 21], though the exact incidence is not known. EMS and first responders should also be aware of the potential safety risk of unmasking of other drug intoxications (methamphetamine, cocaine, or other stimulants) leading to behavioral disturbances. LEO training in naloxone administration has been generally well received and initial studies also report low rates of adverse events [33-35]. Overall, prehospital naloxone administration for suspected opioid overdose is considered safe, though the impact of synthetic opioids on the safety profile is unknown.

Naloxone administered to patients with synthetic opioid overdoses may require multiple doses. During known fentanyl overdose outbreaks, patients have required up to 14mg of naloxone to reverse respiratory and CNS depression [10, 36, 37]. In the prehospital environment, resources can be limited, and a single responding unit or even an entire region may not regularly stock large quantities of naloxone for single patient use. Naloxone supply can be particularly strained during events such as multiple overdose calls for a single responding unit or a multi-day drug overdose outbreak within a single system or area. In a case series of 18 patients, many of whom required naloxone infusions after exposure to fentanyl-adulterated pills, an entire hospital supply of naloxone was depleted and required emergency delivery to replete supply. 83% of patients who had either witnessed or themselves overdosed in the preceding six months reported that two or more doses of naloxone (most commonly used 2mg IN) were required before any response in suspected fentanyl overdoses [38]. Since novel synthetic opioids may have varied street concentrations, potencies, and receptor affinities, the actual dosage of naloxone that may be required to restore adequate spontaneous respirations may be unpredictable. This further emphasizes the role of respiratory support and transport particularly for patients who do not respond adequately to initial attempts at reversal on scene.

Transport

While some studies have failed to demonstrate increased mortality after opioid overdose reversal in the field [39, 40], those who may have overdosed with known or suspected long acting opioids, synthetic opioids, or those requiring repeated doses of naloxone benefit from transport to the nearest emergency department [8, 14]. The safety of refusal of transport after a suspected synthetic opioid overdose has not been established. If spontaneous respiratory drive has not returned after initial resuscitation attempts, EMS should consider transport rather than staying for extended scene times to administer repeated doses of naloxone. En route patient care should include continued reassessment, monitoring, and ongoing respiratory support with repeated administration of naloxone titrated to return of adequate spontaneous respirations, per local protocols.

Awareness of local patterns, collaboration, and community engagement

Synthetic opioids have the potential to overwhelm available emergency resources and supplies, akin to a mass casualty event. EMS systems may mitigate potential strain on local resources by monitoring local epidemiologic patterns, preparing for outbreaks, and collaborating with local agencies, including call centers, law enforcement agencies, EMS/fire departments and EDs. EMS data is particularly well suited for surveillance of suspected overdose patterns as it is geographically indexed and can be collected in near real time [41, 42]. Initial suspicion and tracking of synthetic opioid patterns can involve local EDs, medical examiners, toxicologists, and law enforcement. By sharing knowledge of local trends, all collaborators can stay abreast of the epidemic.

EMS and other first responders are well positioned for a critical role in intervention and prevention, and can provide a unique perspective for community engagement. On-scene interaction with the patient and/or family provides a potentially impactful opportunity to provide resources and support. EMS systems should consider novel strategies for combating the underlying opioid epidemic, including providing on-scene resources, take home naloxone rescue kits, encouraging any local resource utilization including medication assisted treatment (MAT), role of community paramedicine, and other opioid reduction programs.

Additional Resources:

The DEA video with LEO personal accounts of their exposure

Canada's fentanyl safety website

NIOSH recommendations for prehospital PPE

DEA: "Fentanyl, a briefing guide for first responders"

Special thanks to Brooke Lerner, PhD and Jill Theobald, MD

References:

1. United States Drug Enforcement Administration National heroin threat assessment summary—updated. (June 2016). Retrieved Feb 25, 2017. www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2016/hq062716attach.pdf

2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L: Increases in Drug and Opioid Involved Overdose Deaths-United States, 2010-2015. December 30, 2016 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452

3. Deaths Involving Fentanyl in Canada, 2009–2014. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-CCENDU-Fentanyl-Deaths-Canada-Bulletin-2015-en.pdf. Published August 2015. Accessed February 25, 2017

4. Sonka, Joe. (2017). Fentanyl was main driver of Louisville’s surge in drug overdose deaths in 2016. [news release] Insider Louisville. February 28, 2017. Accessed May 24, 2017. https://insiderlouisville.com/metro/fentanyl-was-main-driver-of-louisvilles-surge-in-drug-overdose-deaths-in-2016/

5. Ohio Hamilton County Heroin Coalition: Public Health Announcement: Synthetic Opioid Carfentanil Found in Local Drugs. December 5, 2016. Retrieved Feb 25, 2017 www.hamiltoncountyhealth.org

6. Medical Examiner Public Health Warning Deadly Carfentanil Has Been Detected in Cuyahoga County [news release]; Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner; August 17, 2016. Accessed Feb 25, 2017, http://executive.cuyahogacounty.us/en-US/ME-Public-Health-Warning.aspx

7. Faul, M., Lurie, P., Kinsman, J. M., Dailey, M. W., Crabaugh, C., & Sasser, S. M. Multiple Naloxone Administrations Among Emergency Medical Service Providers is Increasing. Prehospital Emergency Care, 2017; 1-8

8. Lucyk SN, Nelson LS. Novel Synthetic Opioids: An Opioid epidemic within an opioid epidemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Jan;69(1):91-93

9. Martin M, Hecker J, Clark R, et al. China White epidemic: an eastern United States emergency department experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(2):158-164

10. Schumann H, Erickson T, Thompson T et al. Fentanyl epidemic in Chicago, Illinois and surrounding Cook County. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(6):501-506

11. Boddinger D. Fentanyl-laced street drugs “kill hundreds”. Lancet 2006;368:569-570

12. Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid involved deaths-27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep August 26, 2016;65:837-43

13. Fentanyl and Fentanyl Analogs. National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS) Special Report. https://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/NDEWSSpecialReportFentanyl12072015.pdf Published December 7, 2015. Accessed February 25, 2017

14. Sutter ME, Gerona R, Davis M, et al. Fatal fentanyl: One pill can kill. Acad Emerg Med. 2017 Jan;24(1):106-113

15. Armenian P, Olson A, Anaya A, Kurtz A, Ruegner R, Gerona RR. Fentanyl and a Novel Synthetic Opioid U-47700 Masquerading as Street “Norco” in Central California: A Case Report. Ann Emerg Med 2017 Jan;69(1):87-90

16. United States Drug Enforcement Administration Counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyls: A global threat. (July 2016). Retrieved Feb 25, 2017, from www.dea.gov/docs/Counterfeit%20Prescription%20Pills.pdf.

17. Novel Synthetic Opioids in Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals and other Illicit Street Drugs. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-CCENDU-Novel-Synthetic-Opioids-Bulletin-2016-en.pdf Published June 2016, Accessed February 25, 2017

18. CDC health update: influx of fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills and toxic fentanyl-related compounds further increases risk of fentanyl-related overdose and fatalities. (Aug. 25, 2016.) U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved Feb 25, 2017, from https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00395.asp.

19. Drug Enforcement Administration Report: DEA Issues Carfentanil Warning to Police and Public. September 22, 2016. Accessed Feb 25, 2017. https://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2016/hq092216.shtml

20. Riches JR, Read RW, Black RM, Cooper NJ, Timperley CM. Analysis of clothing and urine from Moscow theatre siege casualties reveals carfentanil and remifentanil use. J Anal Toxicology 2012 Nov-Dec;36(9):647-56

21. Helander A, Backberg M, Beck O. Intoxication involving the fentanyl analogs acetylfentanyl, 4-methoxybutyrfentanyl and furanylfentanyl: results from the Swedish STRIDA project. Clinical Toxicology 2016;54(4):324-32

22. Mounteney J, Giraudon I, Denissov G, Griffiths P. Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe. International Journal of Drug Policy (2015) 26:626-631

23. Mohr AL, Friscia M, Papsun D et al. Analysis of Novel Synthetic Opioids U-47700, U-50488 and furanyl fentanyl by LC-MS/MS in Postmortem Casework. J Anal Toxicol 2016;40(9):709-717

24. Coopman, V, Blanckaert P, Van Parys G, et al. A case of acute intoxication due to combined use of fentanyl and 3,4-dichloro-N-[2-(dimethylamino)cyclohexyl]-N-methylbenzamide (U-47700). Forensic Sci Int 2016; 266-68-72

25. Reichard AA, Marsh SM, Tonozzi TR et al. Occupational Injuries and Exposures among Emergency Medical Services Workers. Prehosp Emerg Care 2017 Jan 25 [Epub ahead of Print]

26. Drug Enforcement Administration Report: DEA Warning to Police and Public: Fentanyl exposure Kills. June 10, 2016. Accessed Feb 25, 2017. https://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2016/hq061016.shtml

27. Drug Enforcement Administration: Fentanyl, A Briefing Guide for First Responders. Accessed June 12, 2017. http://dig.abclocal.go.com/wls/documents/DEA_Fentanyl_Publication.pdf

28. Connors NJ, Nelson LS. “The Evolution of Recommended Naloxone Dosing for Opioid Overdose by Medical Specialty.” J Med Toxicol. 2016 Sep;12(3):276-81.

29. Dowling J, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CM, Naidoo D, Graudins A. “Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal naloxone in human volunteers.” Ther Drug Monit. 2008 Aug;30(4):490-6.

30. Merlin MA, Saybolt M, Kapitanyan R et al. Intranasal naloxone delivery is an alternative to intravenous naloxone for opioid overdoses.

31. Belz D, Lieb J, Rea T, Eisenberg MS. “Naloxone use in a tiered-response emergency medical services system.” Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006 Oct-Dec; 10(4):468-71.

32. Buajordet I, Naess AC, Jacobsen D, Brørs O. Adverse events after naloxone treatment of episodes of suspected acute opioid overdose. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004 Feb;11(1):19-23.

33. Ray B, O’Donnell D, Kahre K. Police officer attitudes towards intranasal naloxone training. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015 Jan 1;146:107-10

34. Purviance D, Ray B, Tracy A, Southard E. Law enforcement attitudes towards naloxone following opioid overdose training. Subst Abus 2016 Aug 11:1-6 [Epub ahead of print]

35. Fisher R, et al. Police officers can safely and effectively administer intranasal naloxone. Prehosp Emerg Care 2016;20(6):675-80.

36. Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(2):146-155

37. Solomon, Ranee. A 20-year-old woman with severe opioid toxicity. Journal of Emergency Nursing, April 2017 [Epub ahead of Print]

38. Somerville NJ, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, et al. Characteristics of Fentanyl Overdose- Massachusetts, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:382-386

39. Wampler DA, Molina DK, McManus J, et al. No deaths associated with patient refusal of transport after naloxone-reversed opioid overdose. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15(3):320–324.

40. Kolinsky D, Keim SM, Cohn BG, Schwarz ES, Yealy DM. Is a prehospital treat and release protocol for opioid overdose safe? The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;52(1):52-58.

41. Garza, A and Dyer, S. EMS Data Can Help Stop the Opioid Epidemic. JEMS, Nov 2016. Accessed Feb 25, 2017.

42. Moore, PQ, Weber J, Cina S, Aks S. Syndrome surveillance of fentanyl-laced heroin outbreaks: Utilization of EMS, Medical Examiner, and Poison Center databases. Am J Emerg Med 2017 May 8